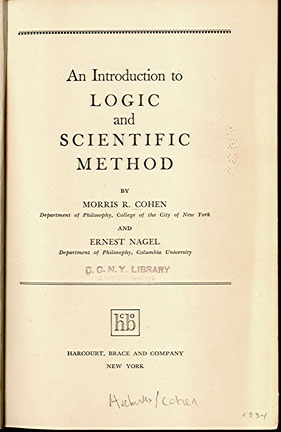

Morris R. Cohen in Retrospect

By Ernest Nagel

Cohen himself confessed that he never felt quite at home

in even the grandest intellectual mansions which philosophers

have been constructing for several millennia. He found no

evidence whatsoever for the frequently made assumption that

the universe is a unitary process, or even a closely knit

pattern of different processes, which conforms to the categorical

schemata of any of the past of current philosophical systems.

He rejected as utterly provincial attempts to map the contours

of existence in terms of anthropomorphic notions, which pretend

to find a likeness to human characteristics in all areas of

nature And while he saw no inevitable progress in the events

of human history, he found no cause either for lachrymose

agonizing or for romantic postures of defiance, in the fact

that the cosmos is not especially arranged for the furtherance

of human aims.

Cohen was therefore no philosophical system builder in the

grand manner. But to my mind he was something much more valuable.

He was a man with an almost insatiable intellectual curiosity,

highly sensitive to the variety of colored strands with which

the web of existence is woven, and possessing an extraordinarily

acute critical faculty for exploding the pretentious shams

of our society as well as of the intellectual life. He liked

to refer to himself as being primarily a logician. But he

prepared himself for the function he believed a philosopher

should exercise, not only by learning the conventional skills

of the logician's craft, but also by acquiring unusual mastery

over a tremendous range of disciplines and materials. He had

a consuming interest in both the natural and the social sciences,

in logical theory as well as in history, in mathematics and

also in law and social philosophy. In consequence, philosophy

as practiced by Cohen was a ancient credos to win assent for

ideas foreign to the accepted meanings of the terms used.

Cohen was a genuine liberal, in matters intellectual as well

as political. He stressed the importance of exploring in a

responsible manner untried possibilities, alternative to those

realized in actual beliefs and actions; and he accepted as

part of his own outlook Justice Holmes's dictum "To have

doubted one's own first principles is the mark of a civilized

man." But Cohen's liberalism was not a spineless eclecticism,

which refuses to take a stand on any issue on the specious

ground that since every distinct perspective reveals something

not visible in another, no perspective whatsoever can be rightfully

adopted. The absolute and total truth is a matter that may

be of concern to an Infinite Intelligence; but it was part

of Cohen's wisdom to be gladly reconciled to our actual human

finitude, and to accept therefore without demurrer the incomplete

yet frequently adequate character of the knowledge of things

we may achieve. Cohen's liberalism was the liberalism of a

critical sanity, which was undismayed by the clamors of the

market place. He was a knight errant in the cause of human

enlightenment, and on behalf of the ideal of beliefs clearly

formulated and rationally established. It is an ideal from

which men often turn away, but it is also one to which many

men frequently return. It is his service to this ideal which

keeps Cohen's memory lustrous, and which calls forth our homage

to him. *

Columbia University.

* "An Hour of Commemoration and Song,"

January

20,1957, at the Temple Emanuel, New York City.

Earnest Nagel, "Morris R. Cohen in Retrospect,"

Journal of the History of Ideas, 18 (Oct. 1957),

pp. 548-551.

Morris R. Cohen helped to launch the Journal of the History

of Ideas in 1939. Cohen served as one of the original

editors and as a reviewer.