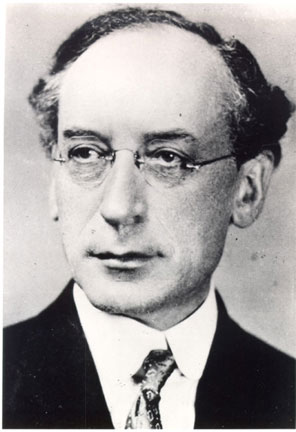

Morris Raphael Cohen was an agnostic, despite

the fact that he was introduced as a child to the traditional

Judaic veneration for learning as well as a certain piety of

spirit that remained with him throughout his life. His idea

of scientific method emphasizes hypothesis, experiment, and

systematic doubt. For no hypothesis is more than probable, though

truth is our aim. Its principal expressions are theories that

assemble apparently disparate facts by specifying their common

character and relations. This conceptual cycle—hypothesize,

experiment, then rethink organizing ideas if an hypothesis is

falsified by the data—is also appropriate to legal and

moral practice. For we don’t know what is best to do or

not do, until experience has established the conditions for

human well-being. This, Cohen’s pragmatism, abuts his

realism and his moral sense. He never doubted that nature has

an established form, one that we can know. Nor did Cohen doubt

that well-being has conditions and characteristics that are

universal, whatever the specificities of particular cultures.

Some of them facilitate, others impede human improvement, though

perfectibility is everywhere possible. Thought—critical,

self-critical intellect—is the only reliable way to achieve

it.

Dr. Cohen's collection contains essays written over the past

twenty-eight years, but united by a pervading largeness of spirit,

graciousness of style, and consistency of viewpoint. They reflect

their author's profound devotion to the liberal temper, which

he conceives not as a specific economic or political creed,

but as "a faith in enlightenment, a faith in a process

rather than in a set of doctrines, a faith instilled with pride

in the achievements of the human mind, and yet colored with

a deep humility before the vision of a world so much larger

than our human hopes and thoughts."

The unique characteristic of liberalism, he believes, is its

commitment to skepticism, to tolerance, to free inquiry, to

the methods and principles of nationalism. "In the end,

there is no way in which people can live together decently unless

each individual or group realizes that the whole of truth and

virtue is not exclusively in its possession." Nor is liberalism

the product of any special economic or political circumstance.

It is "older than modern capitalistic economics. It has

its roots in the Hellenic spirit of free critical inquiry which

laid the foundations of the sciences on which modern civilization

rests."

Arthur M. Schlesinger, Jr. "

Where Liberalism is Vulnerable,"

Commentary, 2, No. 3 (Sept. 1946), p. 250. This review of

The

Faith of a Liberal, Selected Essays by Morris R. Cohen

summarizes Cohen's definition of liberalism in his own words.

Arthur M. Schlesinger, Jr. retired from the Albert Schweitzer

Chair in the Humanities, City University Graduate Center,

Department of History in 1996. He served as a special assistant

to President John F. Kennedy and was a member of the Society

of Fellows at Harvard University from 1939 to 1942.